FISHER-PRICE ORANGEVILLE AND THE WOMEN’S STRIKE, 1968

WOMEN’S MOVEMENT IN THE 1960s

The 1960s was the start of the second wave of women’s movements (sometimes called the feminist movement) in Canada, which saw peaceful demonstrations seeking equality in education and employment, access to birth control, and an end to violence against women.

Girls and women were restricted in employment opportunities, which was also directly linked to limited education. Unpaid household and childcare labour were largely seen as women’s jobs. Women also often worked in the service industry, healthcare, teaching or secretarial roles, which were low paying jobs with very little benefits or none at all. So, it is unsurprising that there was an increase in strikes and protests to demand fair wages and benefits in the 1960s. It was during this time when women who worked at the Fisher-Price factory in Orangeville went on strike to demand on-par wages of their male counterparts.

HISTORY OF FISHER-PRICE

Fisher-Price was founded in East Aurora, New York in 1930 by Herman Fisher, Irving Price, Margaret Evans Price and Helen Schelle. The company’s name is a combination of 3 of the 4 founders’ last names. They sold their first toy, Dr. Doodle, in 1931 and were best known for their Little People toys.

In November 1964, the company purchased the Monarch-Master factory located at 95 John St. in Orangeville and began retrofitting it for a toy factory. According to Herman Fisher, it was due to “the friendly co-operation of town officials, local busines [sic] representatives and townspeople” that Orangeville was chosen as the company’s first Canadian factory (Orangeville Banner, November 1964). Fisher-Price hoped to create a similar team to its East Aurora plant; the success of which was claimed to be due to the cooperative nature of employees and “sharing in company profits” (Orangeville Banner, November 1964). Production officially began in the spring of 1965.

Three years later the plant closed permanently and Fisher-Price focused on its American plant in East Aurora. Irving Price retired in 1969, the same year the company was acquired by The Quaker Oats Company. In 1991, Fisher-Price gained its independence and became a publicly traded company, however by November 1993 it was bought by Mattel. Since 1997, Mattel has marketed all its pre-school toys under the Fisher-Price name.

STRIKE AT THE ORANGEVILLE PLANT

The shutdown of Fisher-Price’s factory in Orangeville came after an 18-week labour dispute. Of the plant’s 90 workers, the majority were women who were paid less than men who did the same work. In 1965, Ontario’s minimum wage was $1 per hour. In that same year, according to Statistics Canada, females in the manufacturing industry made on average $1.41 per hour while males were paid $2.33 per hour.

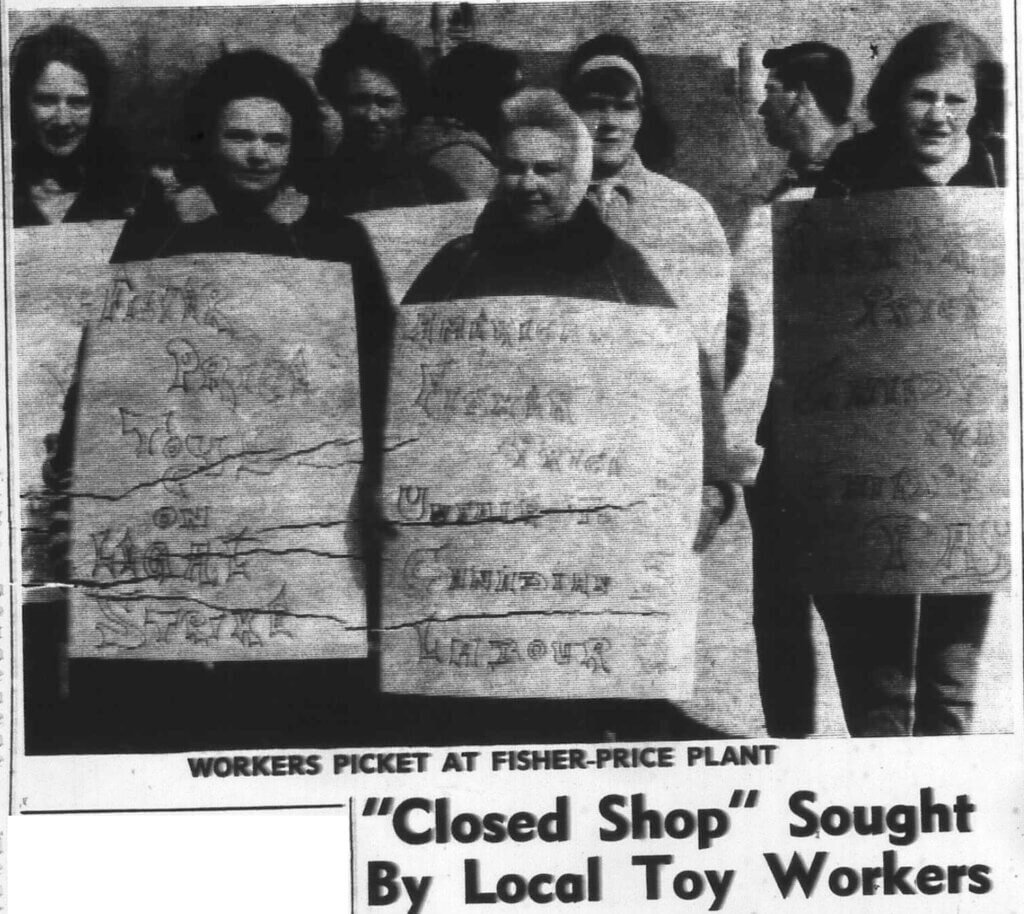

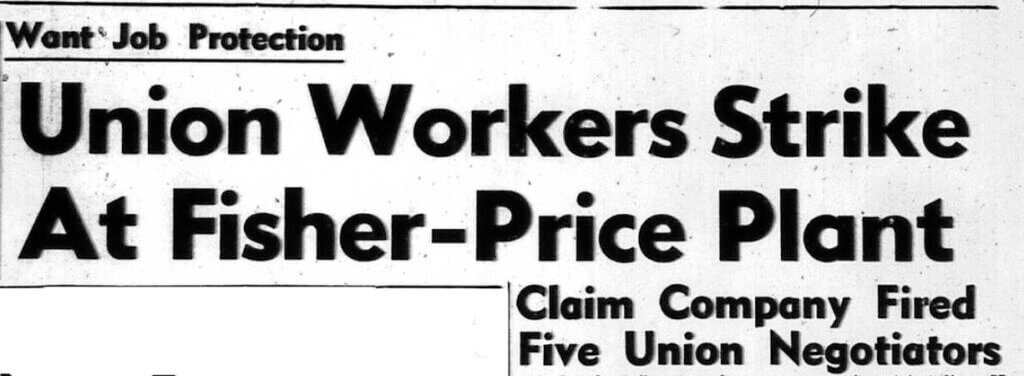

The workers at Fisher-Price were initially part of an Association, but later unionized under Local 905 of the International Toy and Doll Workers Union. The union had at least 10 meetings with Fisher-Price executives to negotiate better pay, a 2- or 3-year agreement, benefits and job protection (Orangeville Banner, April 11, 1968). There was also mention of the union wanting all current and future employees at the plant to join the union. When no progress was made, an overwhelming 98% of union workers voted to go on strike, beginning April 10, 1968. A strike was further fueled by claims that Fisher-Price fired 5 union negotiators (Orangeville Banner, April 11, 1968).

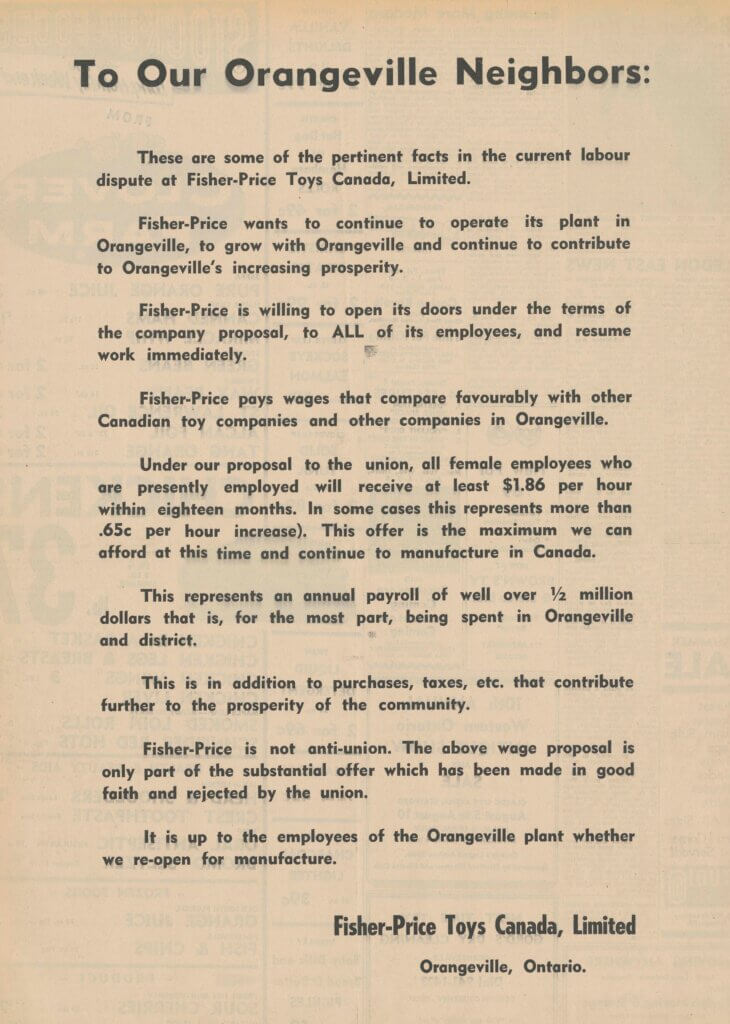

The strike quickly became intense, with the union flying picketers to Fisher-Price’s plant in East Aurora where 24-hour pickets were established. Although employees at the East Aurora plant were not unionized, the union hoped to stop delivery trucks and bring to attention the labour issues at the Orangeville plant (East Aurora Advertiser, May 9, 1968). Despite many meetings there was no progress, so Fisher-Price went public about the strike. They placed an ad in The Orangeville Banner with an offer to increase female employee wages by more than $0.65 per hour within 18 months and some other benefits. They stated that it was the most they can afford in order to continue manufacturing in Canada and that they are not anti-union. The Union rejected the offer as it meant that female employees were still being underpaid compared to their male counterparts. Soon after, a rumor began circulating through the town that the plant was closing. In response, Lloyd Temple, Plant Personnel Manager, told The Banner that the rumors were “definitely false” (Orangeville Banner, August 1, 1968). A week later, on August 15, 1968, The Banner reported on the closure of Fisher-Price’s Orangeville plant.

The company stated that the closure was due to effects of tariff and trade talks, which took place between 1964 and 1967 in Geneva, Switzerland. However, it is likely that the closure was due to the strike and the factory being shut down for more than 4 months.

FIRST HAND ACCOUNTS

The above summary of the strike is based on articles written in local newspapers in 1968, which only told one side of the story – that Fisher-Price was not paying employees fair wages or providing job protection. However, after the MoD reached out to the community in late 2022, past employees came forward with stories of positivity and good memories of their time at Fisher-Price. One of these former employees worked at Fisher-Price as a student for two summers. Her father was the General Manager at the Orangeville plant.

Her experience at Fisher-Price was a positive one; employees were paid and treated well by the company. She was paid about $1.50 per hour (as a student) working on the assembly lines, which was higher than the national average for women working in the manufacturing industry around that time (see above). Employees were always given their full breaks and not penalized for being late and got along very well with the General Manager. Once a year, Fisher-Price would take all the staff and their families on a day trip. One such trip was to the amusement park on Grand Island on the Niagara River. It was privately rented for the day by Fisher-Price, and everything was free, including rides and food.

According to the former employee, the labour dispute was never about equal pay as she believed that men who were being paid more were doing more labour intensive work, such as heavy lifting, whereas all the women were working on assembly lines. After a strike was called, picketers would march up and down the street where the factory was located, and only a couple doors down from where this individual and her family lived. One night, picketers came to her home and started throwing rocks at the house and did the same to the homes of other managers. This event was not reported by local newspapers. When the plant closed, the General Manager was offered a job at the US plant, but he turned it down not wanting to move the family.

There are surely many more first-hand accounts of workers’ experiences that did not make it to the newspapers. If you or someone you know worked at Fisher-Price and would like to share their story, please get in touch with us!

CONCLUSION

Although Fisher-Price ultimately chose to close their Canadian plant instead of agreeing to union demands of better pay and job protection, its presence did have a positive effect on Orangeville. Fisher-Price came to Orangeville at a time when the town’s manufacturing industry was growing. It provided jobs to locals, many of them women, and brought in workers from outside the town. Many of the 30 toys that Fisher-Price produced at the time were bought and used by locals and have now become nostalgic.

The Museum of Dufferin has 14 of the 30 toys produced at the Orangeville plant. You can see the collection on our website (click here).

FUN FACT – If you have any older Fisher-Price toys, look at the bottom. It may be marked “Made in Orangeville”, which means it was made between 1965-1968 in Orangeville.

By: Sahana Puvirajasingam

Sahana is on a contract as the Community Collections Curator at the Museum of Dufferin. She is a Tamil-Canadian emerging museum professional with an MA in History from University College Dublin.

Questions about Collecting the Community can be directed to Sarah Robinson (Curator) by email at srobinson@dufferinmuseum.com or by phone at 519-941-1114 ext. 4019.